Archives on a Damaged Planet: Unruly Ghosts Are Out To Roam

While reproductive labor—such as nursing, cleaning, and care labor—sustains our lives, it is widely undervalued and subject to exploitation in our everyday environments and economies. As such, it is no surprise that this kind of labor is rarely documented in archives. Nevertheless, reproductive labor not only takes up a crucial role in archiving, but also in the production of planetary histories and futures. In its multiple invisibilities, reproductive labor plays a ghostly part in our lives, our archives, and for this damaged planet. It is the ghosts of ongoing struggles of reproductive labor whom we want to address!

This article grapples with the planetary entanglements of ghosts, reproductive labor, and archives. In particular, it focuses on a selection of photographs from the image archive of the Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) in Vienna and the Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez in Mexico City. Both of them are, in their own ways, haunted by past undocumented or unvalued reproductive labor. Ghosts of reproductive labor haunt these archives for what is lost, yet hardly ever existed: the documentation of care work and the masses of people performing it. These ghosts can no longer call for their documentation, but they can invite those who seek them to conspire with them and conjure up imaginaries for their pasts, presents and futures. In the face of Living on a Damaged Planet (Tsing, Swanson, Gan, Bubandt, 2017), these ghosts demand a reckoning with how we care for each other and our surroundings. They urge us to recall knowledges, practices, and sensibilities that lie hidden in the long shadows cast by us humans who have become a major environmental force, having caused climate change and rising sea levels, the pollution of land, water, air, huge landfills, and the extinction of living environments.

In their influential text “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring,” Joan C. Tronto and Berenice Fisher define caring as “a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web” (1990, 40). In our times of concurrent ecological crises, Tronto and Fisher’s understanding of the environment as part of a life-sustaining web of care seems urgent as never before. As it has become clear that this damaged planet cannot be sustained without resolute commitment to care and repair, which encompasses the need to acknowledge what can no longer be repaired, that which has become extinct. Such an approach to planetary caring demands that we change the ways we conceive of, organize, and distribute care labor in our everyday lives. In our efforts to give care to the planet, we need to find “connections across the human and more-than-human worlds” (Zechner, 2021) as well as addressing the blatant exploitation endemic to almost any aspect of care work. Otherwise, this planet will not be repaired.

Caring as reproductive labor in feminist-Marxist terms is unequally distributed among feminized and racialized subjectivities and across geographical zones. The exploitation of planetary care is a prevailing injustice. In her essay “Capitalocene, Waste, Race, and Gender” (2019), the decolonial feminist scholar and activist Françoise Vergès shows how the labor of cleaning and caring is feminized and racialized while she unpacks how the Global Norths construct a “clean”/“dirty” dichotomy between different geographical zones. Their images of “cleanliness” are being maintained by the present-day colonial practice of shipping waste to the Global Souths. Vergès also describes how the conditions of cleaning and care labor intersect with multiple asymmetries of gender, class, racialization, slavery, and migration status—constituting marginalized forms of subjectivity and severe depletion of agency. It is important to stress that these asymmetries are historically grown, and that contemporary modes of exploitative commodification of care work are built on centuries of the modern/colonial, capitalist/patriarchal world-system.

In times of a damaged planet, the mechanisms of this world-system are sure to summon yet more ghosts—in particular, ghosts of reproductive labor and mass extinction of all kinds of species. Their assemblies, however, differ greatly in size, appearance, and haunting depending on where they show up on this planet. In this sense, the feminist sociologist Avery Gordon (2008, 64) calls us to:

“look for lessons about haunting when there are thousands of ghosts; when entire societies become haunted by terrible deeds that are systematically occurring and are simultaneously denied by every public organ of governance and communication; when the whole purpose of the verbal denial is to ensure that everyone knows just enough to scare normalization into a state of nervous exhaustion.”

We, Nina and Julia, the authors of this text, two queer-feminist Austrian majority citizen (Mehrheitsösterreicherinnen*) womxn artists1, have been working together as the Secretariat of Ghosts, Archival Politics and Gaps for more than ten years. Through our work, we have come to consider archives—including their spaces, materials, and caretakers—as ideal sites to look for lessons about haunting. Here we want to introduce you to some of the ghosts we encountered while working with the Archivo (Archive) Ana Victoria Jiménez and the Bildarchiv der Arbeiter-Zeitung (Image Archive of the Workers’ Newspaper).2

Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez, Mexico City

In 2009, a group of scholars and artists, consisting of the feminist art historian and curator Karen Cordero and the feminist artist Mónica Mayer along with the researcher Paz Sastre, curator Lucia Cavalchini, and art historian Daniela Cruz, began to “reactivate,” as they called it, the archive of Ana Victoria Jiménez in order to negotiate its transfer to the Ibero (Universidad Iberoamericana). In 2011, the time had come and the photographer, publisher, and self-declared feminist Ana Victoria Jiménez (born in Mexico City in 1941) transferred her precious visual archive from her house to the Biblioteca Francisco Xavier Clavigero of the Ibero.3

Even though her archive has only recently become more widely recognized, it was at the beginning of the 1970s when Jiménez’ passion for photography started. While Jiménez was participating in several feminist actions, she felt the urge to document them using photography. Concurrently, Jiménez began to collect graphic ephemera, such as posters, flyers, and documents. Without her care and persistence in documenting actions and collecting materials from the 1970s to 1990s as well as the aforementioned group’s “reactivating” efforts, today, it would not be possible to explore and un/learn from the more than 8700 holdings that document feminist concerns, art, actions, and protests (Inclán Cienfuegos, 2019). Today, the university library is committed to maintaining the Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez. For the time being, neither the loan nor the reproduction of Jiménez photographs has any costs associated with them as the university library is interested in their widest possible dissemination. The archive’s multiple feminist ghosts are thus out to roam this planet. What is the future of these feminist ghosts? Or are they from the future? How can we conspire with them?

Selection of Cuaderno de tareas (Assignment Book, 1978-81), A.V.J. Archive Iberoamericana University, Courtesy by Ana Victoria Jiménez.

This is a selection of images from the photographic essay Cuaderno de tareas (Assignment Book, 1978-81) in which Jiménez documents the reproductive labor of two women from different generations in Mexico City, focusing exclusively on their hands as they undertake a variety of tasks: cooking, cleaning the bathroom, washing and folding clothes, ironing, typing, washing and feeding a child, using a sewing machine, knitting, shopping, and taking care of plants.

Cuaderno de tareas (Assignment Book, 1978-81), A.V.J. Archive Iberoamericana University, Courtesy by Ana Victoria Jiménez.

Let us linger a bit longer on the latter. In the photograph, you see hands caring for a Chlorophytum comosum plant, also called Curatodo [Cures All] or Mala madre [Bad Mother] in Mexico. These common names describe the plant’s curing properties—from treating bronchitis, cough, fractures, and burns, and antitumor potential to purifying polluted air (Braria, Shoaib, Harikumar, 2014; Rzhepakovsky et al., 2022, Gawrońska and Bakera, 2015). They also refer to the plant’s reproduction process: the plant produces shoots, releasing them to the soil without providing them with any more sustenance. As the plant does not invest time and energy in caring for its offspring, it is referred to as a bad mother. The plant’s common name entrenches gender-stereotypical expectations and demands! Along with the specters of the “good”/”bad” mother, ghosts of extinct insects haunt the Chlorophytum comosum.4 To make matters worse, it is in critical danger of losing one of its related species, the medicinal herb Chlorophytum borivilianum from India: “unsustainable collection practice, population declines, and low density of the plant indicate that species may become extinct shortly if immediate and appropriate measure are not taken” (Habibi, Joshi, Purohit, 2021, 262). Beyond collection practices, what other forms of human and more-than-human entanglements could be envisioned?

In 2018, a group of students of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in Mexico City got together to create what they call a Power Plant to generate energy from Chlorophytum comosum plants to recharge mobile phone batteries.5 One student, Valeria Nefti Aceves Olalde, explained that it would be important to install these power plants in agricultural areas as an alternative source of energy, as well as in streets, public buildings, and parks for lighting. While the ghosts of the “good”/“bad” mother are still among us, such human and more-than-human entanglements hold the promise that the name mala madre will eventually fall out of use and the plant will be called differently as it provides energy for humans without further damaging the planet.

Jiménez’ photograph carries ghosts where the past is still with us; it leaves a trace of an entanglement of human and more-than-human histories of reproductive labor through which curing properties and energy for humans are made and unmade.

Image Archive of the Workers’ Newspaper, Vienna6

>Aufräumen im Archiv< (2021), SKGAL, still, camera: Ipek Hamzaoglu

>Aufräumen im Archiv< (2021), SKGAL, still, camera: Ipek Hamzaoglu

In this video still, you see us cleaning up and organizing parts of the image archive of the Workers’ Newspaper together with Georg Spitaler. Georg is a researcher at the Verein für Geschichte der ArbeiterInnenbewegung (Association for the History of the Workers’ Movement), the organization taking care of the approximately 600,000 images in the archive. One of the most extensive image archives in Austria, it is housed in the Vorwärts-Haus in Vienna— the same building where the Arbeiter-Zeitung was published by the Vorwärts-Verlag (Vorwärts Publisher) from 1886 to 1991. Among all the images gathered over more than 100 years, we only found a handful showing cleaning labor.7

[They make] visible a history of labor that, although socially indispensable, is mostly performed invisibly in the seclusion of the night and the dawn. Still today, this labor is predominantly done by womxn workers, many of whom have histories of migration. Historically-grown sexist and racist attributions regarding cleaning labor continue to pervade the professionalized cleaning industry. It is still taken for granted that our environment is kept clean, while the labor and bodies behind it go unnoticed. (SKGAL, 2022)

The moment we learned that there was a room full of archival materials at the Vorwärts-Haus waiting to be cleaned up, put into existing or new folders, or thrown out, this opened the possibility of engaging in a barter exchange with the Association.

Instead of using the archive solely as a source, we attempted to work with it as a subject—which meant turning from a predominantly extractive activity to attending the particular form and context (Stoler, 2002). This is why, in our engagements with archives, we seek possibilities to create caring and collaborative relationships that allow for maintaining, continuing, and/or repairing archival practices.

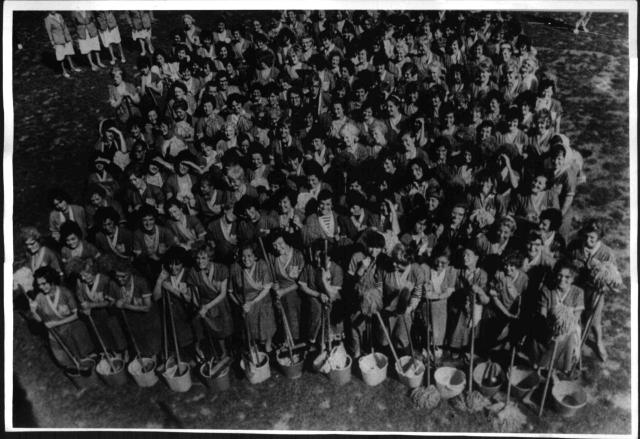

Photos showing cleaning activities (Otto Bartel, 1984; Brüder Basch, 1956, 1966, 1969; Fritz Kern, 1954; Rita Prandl, 1954), VGA, Courtesy of VGA.

Talking with Georg, we agreed to film the process of cleaning and organizing, which was scheduled to last four hours.8 As is typical for this kind of labor, the cleaning took much longer than we expected and did not finish with the fourth hour. Later on, Georg did another round on his own. While he was sorting the last photographs into the appropriate archive drawers he found one more image showing cleaning labor, shot at the Vorwärts-Haus in the 1980s. It belongs to a series of photographs categorized as >Reinigungstätigkeiten< [cleaning activities], which we had found before in the digitized part of the archive.

>Reinigungstätigkeiten< (1984), VGA, photographer: Otto Bartel, Courtesy by VGA.

Attending the ghosts of reproductive labor in and around the Archive of the Workers’ Movements brings up questions of who cleans archives during a struggle or after the uprisings. Who maintains archives of struggles, especially independent ones? How can reproductive labor become part of planetary care—on the streets and in the archives through the entanglement of human and more-than-human worlds?

As we are guests on this damaged planet, with its ecological crises and social and geopolitical asymmetries, how can we collectively look for and bravely face the multiple unruly ghosts of human-instigated destruction?

>Reinigungstätigkeiten< (1963), VGA, Courtesy by VGA.

The following paragraph is from our poster “The Unorganizable Organize Themselves” (2022) produced as part of “HOCH DIE LAPPEN” [“RAISE THE RAGS”]:

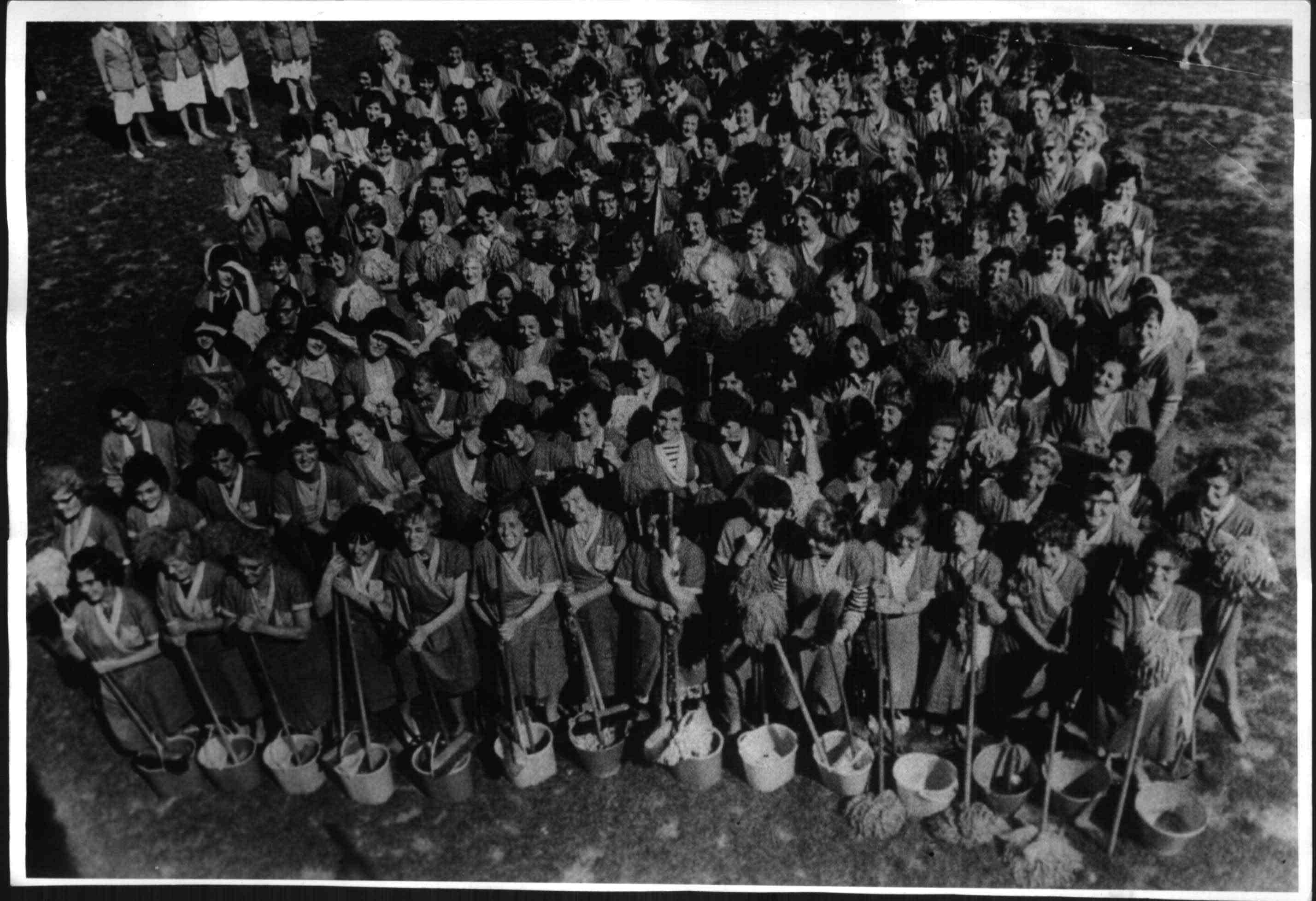

CONSPIRING

Almost 200 people get together. With cleaning buckets, rags and mops, they stepped out of the invisible sphere of their work. People from all over the world who work in the cleaning sector in Europe. Most of them identify as diverse, female, and/or are read as women by us. Many have moved to another country for their work, but there are also some who work where they were born. They work with and without contracts for international cleaning companies, or for their subcontractors, with and without papers, in self-organized cooperatives or for regional administrations, in the household for their own families or for someone else's—often far away from their loved ones. Most of the time, their work is poorly paid or not paid at all.

Despite all their differences, they share the demand for a radical improvement of their working conditions. Cleaning, caring and nurturing runs through all areas of life: through homes, schools, hospitals, elderly people's homes, streets, universities, museums, art spaces, office buildings, airports, train stations, parks, gardens, fields, libraries, and archives; through the cohabitation of people, animals, and plants, as guests on this planet. Cleaners as well as all people who take care of others or care for something, experience it every day: their work is indispensable for human life and planetary survival!

At the get-together, the challenges of a transnational organizational work are immediately considered and addressed: language barriers, country-specific differences of legal and social systems, cross-border commuting to work, isolation in the private home, little or no free time. In such spaces of networking and exchange, the focus is on emancipatory education, mutual support, and forms of cooperation based on solidarity. Private and individual become public, collective, and political. The unorganizable organize themselves and ask: how can we collectively clean, care, nurture and, in doing so, take responsibility for the planet? What would such a world look like?

More:

Thanks a lot to Ana Victoria for your trust and generosity and to Georg for your ongoing hospitality! Thanks to Serena Lee for correcting our English!

Footnotes

1.The term “Austrian majority citizen” (Mehrheitsösterreicher*in) refers to a person who is part of the majority population in Austria, who is White, of Christian background, has German as a first language and holds an Austrian passport.

2.Nina Hoechtl conducted research at the Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez for her contribution on the artist's work to the exhibition “No Master Territories. Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image” at HKW in Berlin in 2022 and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in 2023. SKGAL worked with the Image Archive of the Workers’ Newspaper over the course of three years to develop the two-part installation “HOCH DIE LAPPEN” [“RAISE THE RAGS”] which opened in 2022 at Vorwärtshaus and FLUC in Vienna.

3.After the Art Department of Ibero hosted an exhibition entitled “Mujeres ¿y qué más?: reactivando el archivo de Ana Victoria Jiménez” [Women, And What Else?: Reactivating the Archive of Ana Victoria Jiménez] to celebrate this transfer, it would take until 2019, another eight years, for the Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez to be shown in an exhibition entitled “Mexican Feminism in Protest: The Photography of Ana Victoria Jiménez” at Wadham College in Oxford. In 2022, the archive was part of the exhibition “¡En la calle y en la historia! 40 años de lucha feminista mexicana” [In the Streets and in History! 40 Years of Mexican Feminist Struggle], curated by Julia Antivilo at the Casa del Lago UNAM. The archive provided crucial materials for the exhibition “Indicios de una revuelta artística feminista” [Signs of a Feminist Artistic Revolt], curated by Fernanda Ramos at the Museo de Arte Moderno, among others.

4.In recent years, several scientists have warned of insect extinctions. More than 40% of insect species are declining and a third are endangered. The total mass of insects is falling by a precipitous 2.5% a year, suggesting they could vanish within a century. For more, see Cardoso et al., 2020; Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys, 2019.

5.The group of students consists of Valeria Nefti Aceves Olalde, Edgar Martínez López, Héctor Emanuel Urbina Hernández, and Javier Villegas Jiménez. For more, see Mugs Noticias, “Politécnicos usan Mala Madre para generar energía”. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sociedad/politecnicos-generan-energia-con-la-planta-mala-madre/

6.Parts of the following paragraphs were presented by SKGAL at the panel discussion and film screening “Critical Closeness: A Conversation on Archival Work,“ October 18, 2022 at MUMOK, Vienna.

7.These photographs were activated and edited in our research and installation project entitled HOCH DIE LAPPEN [RAISE THE RAGS], convened in June 2022 at the Vorwärts-Haus and for the Billboards of the Fluc in Vienna. For more, see Instagram: @skgal__

8.Thanks to Ipek Hamzaoglu who was filming and recording the sound and caringly accompanied the whole process!

Bibliography

Braria, Alisha, Shoaib, Ahmad, Harikumar S. L. “Chlorophytum comosum (Thunberg) Jacques: A review.” International Research Journal of Pharmacy, 5(7), 2014: 546-549. http://dx.doi.org/10.7897/2230-8407.0507110

Cardoso, Pedro, Barton, Philip S., Birkhofer, Klaus, Chichorro, Filipe, Deacon, Charl, Fartmann, Thomas, Fukushima,Caroline S., Gaigher, René, Habel, Jan C., Hallmann, Caspar A., Hill, Matthew J., Hochkirch, Axel, Kwak, Mackenzie L., Mammola, Stefano, Noriega, Jorge Ari, Orfinger, Alexander B., Pedraza, Fernando, Pryke, James S., Roque, Fabio O., Settele, Josef, Simaika, John P., Stork,Nigel E., Suhling, Frank, Vorster, Carlien, and Samways, Michael J.. “Scientists' warning to humanity on insect extinctions.” Biological Conservation, Volume 242, 2020: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108426.

Fisher, Berenice and Tronto, Joan C. “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring.” In Circles of Care, ed. E. K. Abel and M. Nelson. Albany: SUNY Press, 1990.

Gawrońska, Helena and Bakera, Beata. “Phytoremediation of particulate matter from indoor air by Chlorophytum comosum L. plants”, Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 8, 2015: 265-272. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4449931/

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Habibi, Nazima, Joshi, Neelu, and Purohit, Sunil D. “Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology of a Critically Endangered Indian Medicinal Herb-Safed Musli (Chlorophytum borivilianum Sant. Et Fernand).” In An Introduction to Medicinal Herbs, New York: Nova Sciences Publishers, 2021.

Inclán Cienfuegos, Luis Héctor. “Archivo Ana Victoria Jiménez del movimiento feminista en México (1970-1990)”, Universidades, núm. 81, 2019: 85-87 http://udualerreu.org/index.php/universidades/article/view/42/40

Mugs Noticias. “Politécnicos usan Mala Madre para generar energía.” Accessed March 7, 2023. https://www.mugsnoticias.com.mx/noticias-del-dia/politecnicos-usan-mala-madre-para-generar-energia/.

Rzhepakovsky IV, Areshidze DA, Avanesyan SS, Grimm WD, Filatova NV, Kalinin AV, Kochergin SG, Kozlova MA, Kurchenko VP, Sizonenko MN, Terentiev AA, Timchenko LD, Trigub MM, Nagdalian AA, and Piskov SI. “Phytochemical Characterization, Antioxidant Activity, and Cytotoxicity of Methanolic Leaf Extract of Chlorophytum Comosum (Green Type) (Thunb.) Jacq.” Molecules. Jan 24;27(3): 762, 2022. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030762.

Sánchez-Bayo Francisco and Wyckhuys, Kris A.G..“Worldwide decline of the entomofauna”, Biological Conservation Volume 232, 2019: 8-27. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320718313636.

SKGAL, “HOCH DIE LAPPEN [RAISE THE RAGS]”, project description, 2022. Accessed March 7, 2023. http://www.skgal.org/hoch-die-lappen-raise-the-rags/.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “Colonial archives and the arts of governance.” Archival Science volume 2, 2002, 87-109.

Vergès, Françoise. “Capitalocene, Waste, Race, and Gender”, e-flux Journal #100, May 2019. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/100/269165/capitalocene-waste-race-and-gender/.

Zechner, Manuela. “To Care as we Would Like to: Socio-ecological crisis and our impasse of care”, The Gropius Bau Journal, 2021. Accessed April 9, 2023. https://www.berlinerfestspiele.de/en/gropiusbau/programm/journal/2021/manuela-zechner-to-care-as-we-would-like-to.html