Haunted by the Wolf

Some Thoughts, Memories, Images and Acts on Presence/Absence of Wolf 1

The wolf is spectral in the “West,” writes Carla Freccero in her great text “Wolf, or Homo Homini Lupus” on the wolf and Western imagination (Freccero, 2017, M102), and I would like to add some thoughts on “the spectral wolf” that haunts human myths also in the “East” and has been doing so similarly in my own creative and intellectual practice for some time.

It was in the winter of 2011 that I realized that wolves are almost exterminated in Western Europe and this was maybe one of the most striking cultural shocks that I experienced since migrating from Belgrade to Vienna and later to Innsbruck. One can say that wolves are extinct throughout Western Europe, even though there are a few wolves here and there. I learned about this while I was on a residency program in the Austrian Alps, in the city of Innsbruck. I spent a lot of time alone, looking out through a work space window at Schloss Büchsenhausen, getting distracted by the ever changing forms of the blue sky clouds during those sunny winter days. I observed with great respect the mountains, thinking about their names and life and history, which resonated for me with some old unknown languages, practices, imaginations (Patscherkofel, Serles, etc). During that stay, I learned that the stunning mountains and forests surrounding the city were not areas of vast wilderness, as they seemed to me, but rather cultivated landscapes shaped by human interests for centuries. It took me some time to understand how humans could manage to take “total” control and power over nature and how an animal that once inhabited almost the entire northern hemisphere could be gone.

Back then, I had no time to engage in deeper research and writing on this topic. I was writing what later became the first chapter of my dissertation on queer, anti-fascism and no-border politics in Belgrade and apart from that, I was overwhelmed by the critical correctness debate on unignoring anti-Semitism in contexts of critical knowledge production in Vienna (Marjanović, 2017; 2012). Additionally, I was going through a very difficult period of migration crisis, so being in Innsbruck and in the Alps was an important moment of break and retreat for me. The surrounding nature had restorative effects and I have kept coming back for years. Places such as forests and mountains, and questions about who lives there have been preoccupying me.

View through the window at Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen. Photo by Ivana Majanović, 2011

Mural in Vienna. Photo by Ivana Majanović, 2013

I grew up in Belgrade on the edge of the town, in a small village-settlement on the foot of the mountain Avala. Standing at 511 meters above sea level, Avala enters the locally defined mountain category just by 11 meters (which is a topic for many local jokes about it being a “mountain”). It hosts some important historic Yugoslav monuments and is a tourist attraction that provides a panoramic view of Belgrade. I spent a great part of my childhood and youth in that nature-culture forest. Arriving in Innsbruck in the fall of 2011, the landscape somehow felt like home: the trees, the snow, the forests, the countryside effect of the alpine city...

As children, my siblings and I would spend spring holidays in the national park of Tara mountain with our mom, kids from the kindergarten where she worked, and our cousins, and we all had a very good time. I remember us hiking, picking flowers and my sister making floral hair wreaths for us. We felt very safe there. None of my memories contain a fear of wolves (now this is surprising for me knowing that, when it comes to wolves, some of the most manipulative arguments in the debate surround the safety not only of flocks but also of human children – the fear inscribed in our cultural memory through fairy tales). However, my mom has always been cautious about where in the forest one can take a walk, as some mountains are “wild” and “you can’t just go wherever you want.”

The “East” of Europe shares with the “West” the “long genealogy of both hostile and proximate human-wolf togetherness” (Freccero, 2017, .m93). In the Balkans, as Sandra Iršević writes on the Ecofeminism blog, the wolf is at the same time interpreted as a predator and as a deity, and it has always had an important place in local folklore, customs, and traditions. Depending on the context, she writes, the wolf is evil and dangerous, or it’s a symbol of strength and power and hence has a protecting power (Iršević, 2016).

“The peoples of the Balkans respected the wolf, even the ancient Slavs represented their supreme god Dažbog in the form of a lame wolf. These animals had a strong symbolism that was preserved throughout the turbulent history, then transferred to the era of Christianity […] A large number of male and female names originated from the words VUK (Vuk, Vukašin, Vujadin, Vuka, Vukosava). It was believed that the wolf drove away evil fairies and ghosts, protected children from plagues and diseases, and small children were given names with the wolf prefix, as a preventive measure.” (Iršević, 2016 [my translation])

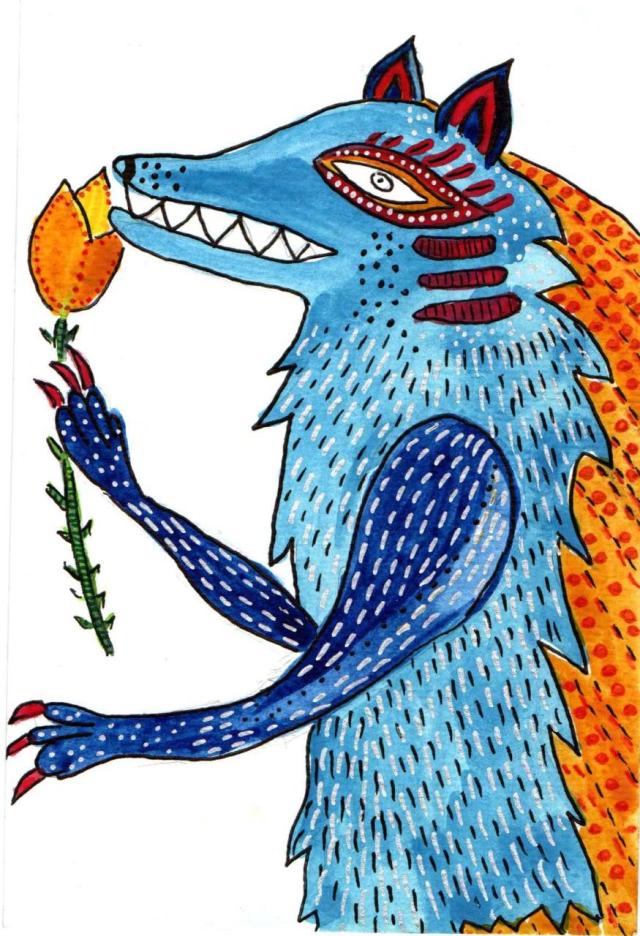

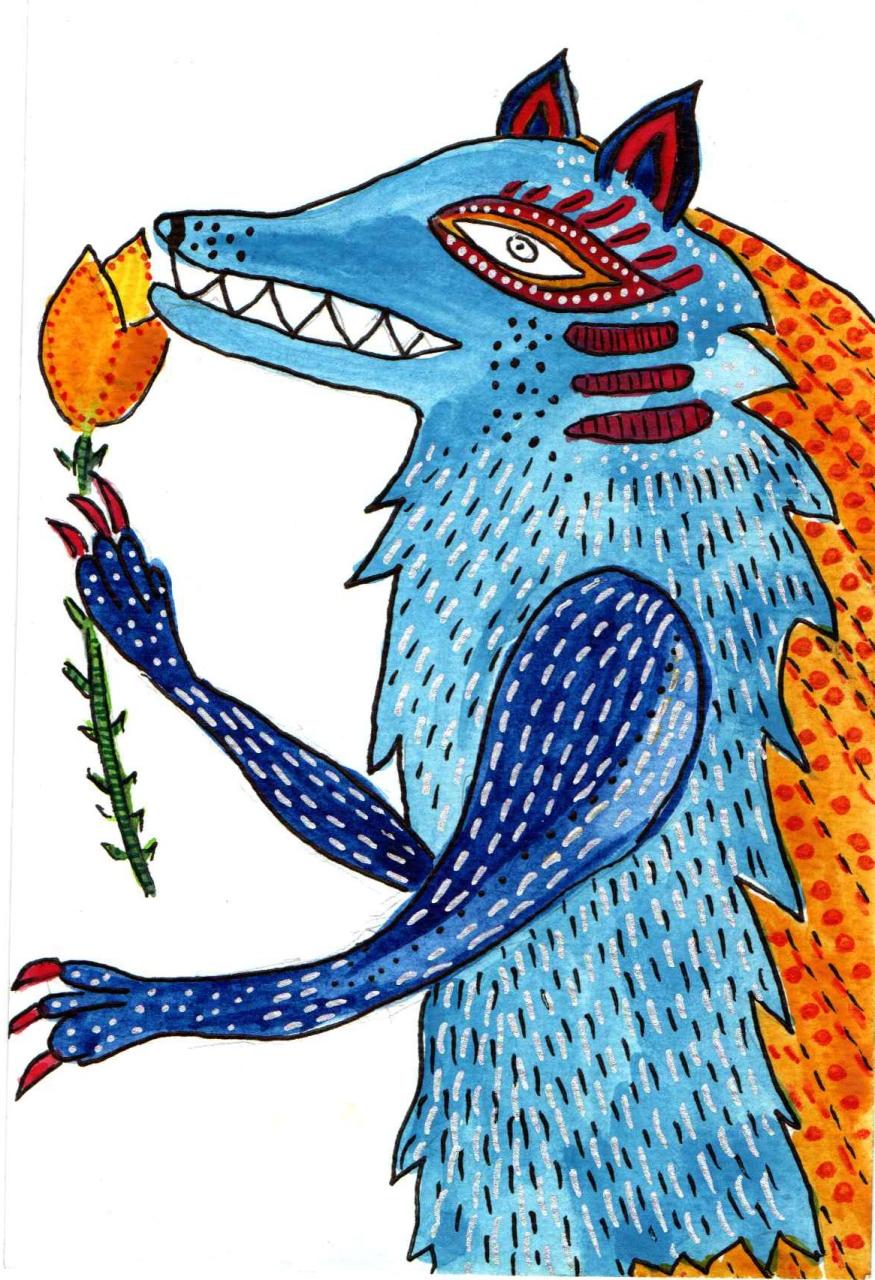

This naming custom is not only an old tradition, but a practice that still lives. Last year one of my closest friends Nataša Mackuljak, a feminist artist, curator, and activist in Vienna gave her new-born daughter the name Vuka (translates as female wolf), as a symbolic performative act of protection but also of praising the animal and even contributing to the struggles around its endangered status. Also deciding on this “archaic” naming act emphasizes female power, empowerment and struggle. I created several drawings in honor of this new life and that naming act as a protection and celebration, and I made some presents for small Vuka but also for some other strong women.

Vuka. Drawing for my Sister, Ivana Marjanović, 2020

Vuka. Drawing for Vuka, Ivana Marjanović, 2020

COHABITATION: ARTISTIC INTERVENTIONS AND VISIONS

On invitation from Marion von Osten2,who was a very dear person and professor and supported me during my dissertation project, and her colleagues from ARCH+ Magazine from Berlin, I curated an exhibition at Kunstraum Innsbruck titled Cohabitation. Space for all Species. The Future of Alpine Cities and the Coexistence of Humans and Animals (April-June 2021)3. The research project and exhibition Cohabitation at Kunstraum Innsbruck considered the specific context of the alpine city as a conflict-ridden home of different species and as a starting point for a futuristic vision of a realm not exclusively dominated by humans: the multispecies city.

As a contribution to the international project, I invited a group of local artists, activists, and researchers to share their critical, humorous, analytical, or poetic works. It seemed to me important to treat this “local” topic politically by involving, among others, artists who live or grew up in a very racist society and hence have developed special relations to animals who became their companions in survival (Ina Hsu and Gina Disobey). Not unsurprisingly these artists created two installations with the title Through Barriers that dealt with solidary existences of marginalized humans and animals.

The wolf had a prominent space in the exhibition and later was also understood as a platform for alternative debates and knowledge production on the absence/presence of the wolf in the context Tyrol and Innsbruck (art works by Nicole Weniger, Patrick Bonato, discussions organized by philosophy students of Michaela Bstieler). As the city borders extend the city up to the mountain tops, it is crucial to critically discuss the appropriation and industrialization of nature, and challenge human exceptionalism, exclusionary "security" measures, and the commodification of the natural world that keeps certain animals out of the “polis”. However, the wolf has been coming back not only through its spectral presence in the cultural imagination, it has also been coming back by crossing, however unsuccessfully, geo-political human borders.

Anti-wolf right wing transparent “Pastures for our cattle, wilderness for wolves” Photo by Ivana Marjanović, 2021

Every summer in the past years, when cattle and sheep are brought to the uncountable Alms of Tyrol, the discussion about wolves flares up. Every now and then a lone wolf (there are no known natural wolf-packs in Tyrol) sneaks in from Italy, Slovenia, or Switzerland and kills some sheep. The loss for some farmers is real but the reaction is often totally exaggerated, considering that there are many dangers for sheep on the Alm and deaths due to wolves are small compared to other causes of death. It also usually does not take long until the “problem-wolf” is illegally shot dead. In addition, this year a big media hysteria broke out after some sheep were killed (even before the “perpetrator” had been confirmed as a wolf), leading to people calling for the shooting of “problem wolves” and a redefinition of what makes a wolf a “problem-wolf” so that it can be legally killed. An anti-wolf lobby (mainly farmers and hunters) currently even propagates fake conspiracy arguments that wolves are secretly set free by eco-activists/”terrorists.” The wolf is now acquiring the status of an alien, the discourse resembles right-wing arguments about jobloss related to the “refugee crisis” (“wolves are a threat to industry workers because they eat meat”). The slogan of the anti-wolf-platform www.almohnewolf.at (linked to the Tiroler Bauernbund) is “Unserem Vieh die Almen, dem Wolf die Wildnis” (Pastures for our cattle, wilderness for wolves), but in reality more or less all of Tyrol is covered by mountain pastures, there is practically no wilderness left.

Nicole Weniger, WANTED, 2021

At the exhibition Cohabitation, with the action Wanted (2021), Nicole Weniger commented on the current public debate on wolves that one can see in the public space in the form of signs, such as “wolves welcome” and “Alpine pastures without wolves.” The abject animal is an object of desire and aversion. The artist deals with ambivalences, fears, and myths around the wolf and asks who can stay and who decides? Referencing the “wanted poster” that depicted “criminals” in the past, she creates a new version that reveals the absurdity of the search for an officially protected animal, which is often immediately (and illegally) killed when it sporadically appears in Tyrol, an animal that most of those discussing never even had a chance to personally encounter in the Tyrolean Alps.

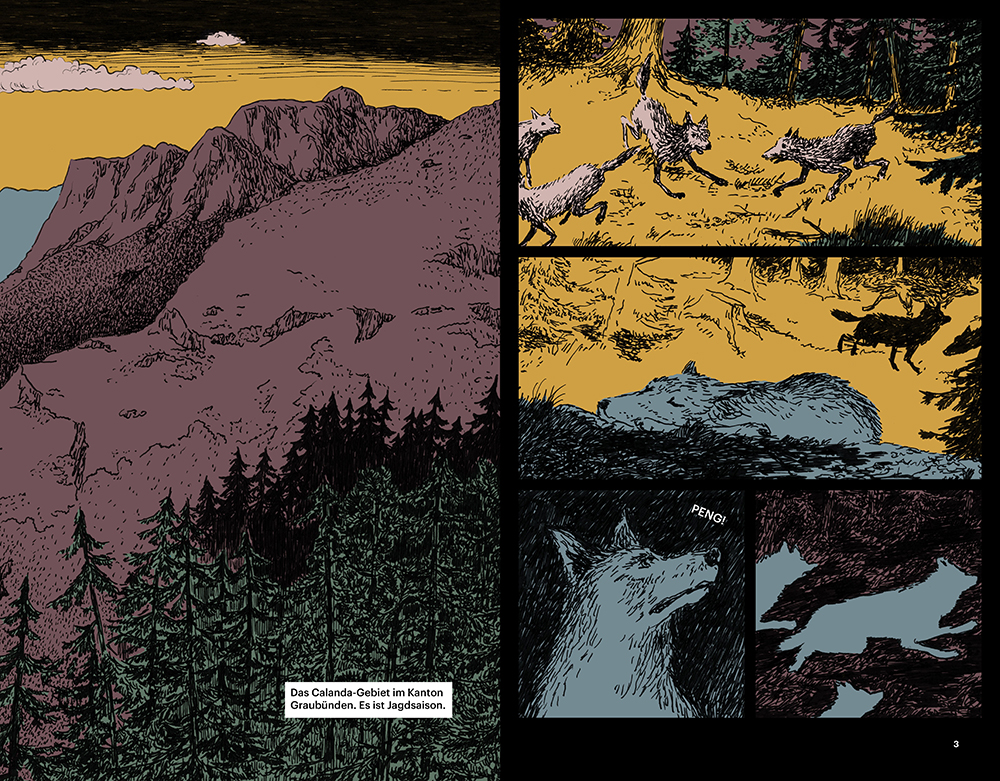

Patrick Bonato, work-in-progress Comic The return of Wolves to the Alpine Cultural Landscape (2021).

Based on the scientific research of the geographer Verena Schröder, the comic by Patrick Bonato brings examples of cohabitation of wolves and humans in other parts of the Alps, namely in Switzerland, contributing to the heated, highly polarized debate. Visualizing moments of contact between wolf and human (hunter), the comic translates the experience of an encounter that changes them both. Going back to some traditional models of pasture protection, wolves do not necessarily have to be enemies of shepherds and hunters. The extinction of mammal predators such as the wolf, lynx, and bear by hunters and farmers has enabled them to assume the role of maintainers of a balanced population of deer and domesticated animals in the first place. Now that small numbers of these pristine carnivores are returning to their original habitats, hunters and farmers seem reluctant to redistribute some of their acquired power of control.

A transparent “Wolves welcome” in Arzl, Innsbruck. Photo by Ivana Marjanović, 2021

The history and presence of the wolf in Europe has been conflictual, also in the East of Europe, where wolves still live. Wolves are hunted, unprotected, admired, protected, romanticized, studied, exhibited... Though it seems unlikely that the mountains with wolves will exist again in the forms they once did (even if wolves were to be reintroduced), it is necessary that we distance ourselves from the dominant human /capitalist domination over nature as it does harm not only to animals but also to human subjectivity. To bring the reflection to a close, I will end with three inputs. The first one is by Fahim Amir, a philosopher I got to know learning from/with Marion von Osten:

„To include the claims of others as part of the equation is to relativize our sovereignty. Participation also means sharing, and so we will have to give up something. For instance, the idea of a completely controllable and ‘manageable’ environment. All life forms inhabiting the planet influence each other in complex ways that are neither fully understood nor controllable. […] Cohabitation, on the other hand, means ‘living with’—something that is not always pleasant, innocent, beautiful, or free of danger. ‘Living with’ fosters the development of neighborhoods, which are the opposite of gated communities, because neighbors are beings whose presence we did not choose.” (Amir, 2021)

In the summer of 2021, two indigenous artists from the Brazilian Amazon territory, Moara Tupinambá and Uýra Sodoma, spontaneously performed a ritual for the return of wolves at the Nordkette in Innsbruck, during their visit for the opening of the exhibition Resurgences of Amazonia! at Kunstraum Innsbruck, co-curated by Marissa Lôbo. The wolf keeps haunting us.

My mom taught us how to move through the forest, respecting it by accepting that it doesn’t belong only to us humans but also to others and hence we cannot take it all.

Moara Tupinambá and Uýra Sodoma. Photo by Ivana Marjanović, 2021.

Bibliography

Amir, Fahim. 2021. “ Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species Cohabitation its Lived Exploration. Manifesto“. ARCH+ Online, https://archplus.net/de/cohabitation-EN/ (accessed July 09, 2021).

Freccero, Carla. 2017. “Wolf, or Homo Homini Lupus.” In: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Eds.: Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan and Nils Bubandt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Estes Pinkola, Klarisa. 2018[1992]. Žene koje trče s vukovima [Women Who Run With The Wolves]. Beorgad: Nova knjiga.

Haraway, Donna. 2020 [2003] The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Le Guin K., Ursula. 2019 [1988] The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. London: Ignota Books.

Iršević, Sandra. 2016. “Vuk: Božanstvo ili predator?” [Wolf: Deity or Predator?], http://www.ecofeminizam.com/2016/04/08/vuk-bozanstvo-ili-predator/ (accessed July 09, 2021).

Marjanović, Ivana. 2012. “Unignoring anti-Semitism in contexts of critical knowledge production” http://unignoringantisemitism.blogspot.com/ (accessed July 09, 2021).

Marjanović, Ivana. 2017. Staging the Politics of Interconnectedness between Queer, Anti-fascism and No Borders Politics. The Case of QueerBeograd Cabaret (manuscript).

Footnotes

1.This text is originally published in a shorter version translated into German language in: PLAYBOOK Klimakultur Strategien für einen nachhaltigen Kulturwandel CREATIVE AUSTRIANS II, Birgit Lurz, Wolfgang Schlag, Thomas Wolkinger (Hg), 2021. Wien: Bundesministerium für europäische und internationale Angelegenheiten – Sektion für internationale Kulturangelegenheiten. https://www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Kultur/Publikationen/Playbook_Klimakultur_Web_20210910.pdf (accessed December 02, 2021).

2. Marion von Osten initiated the project. She passed away in November 2020 and the project is dedicated to her.

3. With works by: Patrick Bonato, Gina Disobey, Ina Hsu, Roland Maurmair, Nicole Weniger and young architecture researchers from the Institute for Design studio 2 (Daniela Albrecht, Bernd Baumgartner & Daniel Alber, Florian Heinrich & Gabriel Kopriva, Sophia Niederkofler, Franzisca Rainalter, Louisa Sommer, Lara Tutsch & Carina Wissinger). Curated by Ivana Marjanović / Kunstraum Innsbruck. In cooperation with Birgit Brauner, Karl-Heinz Machat, Michaela Bstieler and Andreas Oberprantacher / University of Innsbruck & ARCH+ magazine for architecture and urbanism / Berlin. https://www.kunstraum-innsbruck.at/en/archives/exhibitions/cohabitation; https://archplus.net/de/cohabitation/